It’s always a good time to take stock of the year that was, so I’ve been thinking about what 2022 held for me. On a personal and professional level, it was great – doing a job I love with enough work–life balance stirred into the pot for good measure.

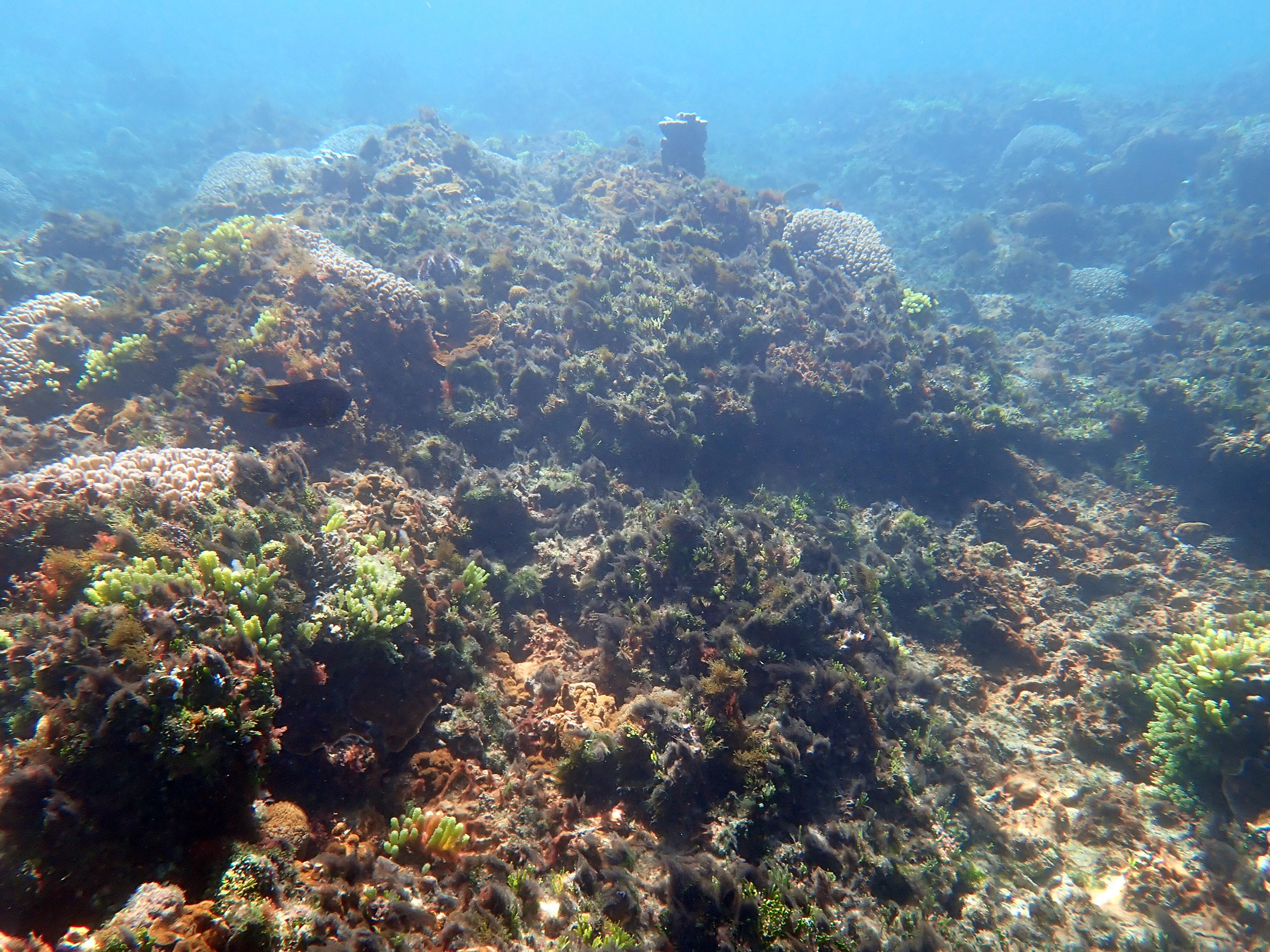

But for Norfolk Island’s reef, I really can’t say the same. La Niña superimposed on La Niña has meant copious rainfall and a lagoon under stress: more algae, more coral disease, fewer fish. Here’s a very brief run down of what has been happening on Norfolk Island’s forgotten reef during 2022.

A year ago I reported on the increase of an algae known as Lyngbya majuscule and the furry little sea hares that feed on them. I wrote about this in the blog post ‘Furry Sea Hares as Eco-warriors’. Here we are a year later and Norfolk Island Regional Council, in association with Norfolk Island National Park, has had to issue warnings about not ‘interacting’ with this particularly nasty alga, because, yet again, it is proliferating in our bay (see social media posts, above).

During the warmer months at the beginning of 2022, we had several algal-bloom events in the water column in Emily Bay. In December 2022, we experienced the first one for this summer season. If you’ve never swum through one of these, imagine swimming through pea soup. It isn’t pleasant. And it is definitely not healthy for the reef.

In February and March 2022, we had another algae sweep across our corals. This time it was a thick choking red mat of cyanobacteria. To say this was heartbreaking is an understatement. I talk about this particular horror in a blogpost called ‘Come on in. The Water’s Fine’.

An alarming drop in sea cucumber and sea urchin numbers was noted by myself and other snorkellers, and by the team of reef researchers to the island. These animals are essential to a balanced ecosystem. If too many are removed, or if they fail to thrive, that is not good. You can see my two blog posts on these two critters here: ‘The Importance of Sea Urchins’ and ‘Heroes of the Beach – Sea Cucumbers’.

Then we had the heartbreaking case of Doris, the green sea turtle. Emaciated, covered in algae and clearly very weak, she was rescued by a group of us and has been in the care of volunteers and staff at the National Parks office since. Hopefully, 2023 will see her return, but to what? You can find out more about her story here ‘#OperationDoris Green Sea Turtle Rescue’, or search for the hashtag #operationdoris.

Sea squirts have been increasing across the lagoonal area. Is this relevant? Is it significant? I don’t know, but there are a lot of them encrusting corals where there were very few previously. I wrote about these here in ‘Sea Squirts – Friend or Foe’.

The researchers who give us the science about what is happening on our reef are quite clear and unequivocal in their assessment: In an article in the Sydney Morning Herald on 20 November 2022, Dr Trace Ainsworth says, ‘the rate of diseased coral in Norfolk Island’s lagoonal reef [i]s now among the highest recorded on an Australian reef.’ You can read more about what the experts say in ‘Norfolk Island’s Forgotten Reef Needs Help’.

Is there any good news?

Well, yes, there is. But it’s a bit like the proverbial curate’s egg. With the good also comes the bad. Professor Andrew Baird, chief investigator at the former ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, estimates that at least 30 per cent of the coral species documented on Norfolk Island are undescribed, thus unknown to science. In other words, a third of our corals could be unique. The downside of that is that we could lose them before we even understand what we have.

I have been raising the matter of our reef with politicians and the government for nearly three years now. In that time, the reef has deteriorated and some beautiful corals have succumbed to disease.

Those who frequent the bays are asking each other, where are all the fish? I am finding it increasingly hard to take decent photographs of some fish because they simply aren’t there anymore or are difficult to find. Here’s is a quick anecdotal assessment:

The bait balls (small juveniles or fry) have been missing in action inside the lagoons this year.

Beneath the raft, once a nursery for all kinds of species, is barren, partly due to Council’s new, improved design, but is there another reason?

The bluespine unicornfish have gone from four adults to one (plus one ‘teenager’ and a few babies).

The pencil surgeonfish have reduced from a small school of eight or nine individuals to two.

The catfish seem to be staying outside the reef more than they are inside.

The schools of mullet are much smaller.

The busily voracious schools of elegant wrasse are noticeably smaller, too.

The small family groups of three and four bluespotted cornetfish are reduced to one or, if you are lucky, two individuals inside the reef.

I last saw a Norfolk Island blenny (only found here on Norfolk Island) in April 2022.

I saw my first leopard flounder since March 2022 a week ago.

Yellowstriped goatfish, cardinal goatfish and blacksaddle goatfish? All reduced in numbers.

I could go on, but I won’t bore you.

Will I be writing in another year’s time that our reef has gone past the point of no return? I sincerely hope not. Let’s hope that 2023 is a much better year for Norfolk Island’s reef.